In last week’s post I busted some myths about the plant-based/vegan diet. It’s the diet that I follow, but it is often confused with the vegetarian diet, especially the important differences between the two diets in terms of practical, ethical, climate impact-related, or health-related issues. They also overlap with one another. Therefore, this week I am going to explain so of the key differences between vegan and vegetarian diets.

Before reading on, please take a moment to check out my Plant-powered Diet Transformation course. This course has been designed to help people to shift to a more healthful, plant-based diet in an interesting, practical, and individually supported way. All of the details can be found on my website at https://thecompletehealthcoach.org.uk/healthy-eating/

Actually, let’s start with the similarities then we can look at the practical differences. Both contain all plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, grains (e.g. wheat, oats), beans and legumes (e.g. lentils, peas), nuts, and seeds. Neither of them include meat or fish.

The main difference between the two comes when we consider dairy products and eggs. People who follow a vegetarian diet do eat dairy (e.g. milk, butter, cheese, yoghurt) and they may also eat eggs, but vegans don’t. Another food that differentiates the two diets is honey. As it comes from bees it can’t be considered to be part of a vegan diet, but it is regularly eaten by vegetarians.

I believe that the vegan diet is the healthiest diet, as long as it is a whole foods plant-based diet and not just a diet that contains vegan versions of the standard junk foods; sausage rolls, pies, cakes, hot dogs, chicken nuggets, pizzas, chocolate bars, and ice cream. Taking a look at the differences between a junk food vegan diet and a whole foods plant-based diet is a topic for another blog, so for now I will begin my detailed look at the differences between vegetarian and vegan diets by considering the effects on our health of not eating dairy produce.

The health benefits of ditching dairy and eggs

One of the foremost authorities on the risk to our health of eating dairy is Prof. Neil Barnard of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) at George Washington University. He lays out the key issues on the PCRM website:

https://www.pcrm.org/good-nutrition/nutrition-information/health-concerns-about-dairy

Firstly, saturated fats. These fats are the ones that can lead to the blocking of arteries and the development of coronary heart disease (CHD). They are largely absent from plant foods (although coconut oil contains high levels), but are common in dairy where they are the top source of saturated fats in the Western diet. Cheese, for example, is typically 70% fat. Therefore, a straightforward way to reduce the chances of developing CHD is to cut out dairy products, including making swaps such as drinking oat or almond milk instead of cow’s milk.

There is also growing evidence that the incidence of some cancers is higher in people who eat dairy compared to those who don’t. For example, research has shown that consumption of dairy products leads to an increase in concentrations for insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a known marker for prostate cancer risk. One study showed that men with the highest levels of IGF-1 had a 4 time greater risk of prostate cancer than those with the lowest levels of IGF-1. In the Physicians Health Study, which tracked over 21,000 people over 28 years, results showed an increased risk of prostate cancer for those who ate more than 2.5 portions of dairy daily compared to those who ate less than 0.5 portions.

Then there is the issue of lactose intolerance. Milk is a food for infants whether they are human babies or cow babies. Once babies have grown past the infant stage they don’t drink mother’s milk any more and their production of lactase (an enzyme that breaks down lactose in the body) diminishes. So far so good, but when human adults continue to drink cow’s milk they can have adverse reactions such as bloating and diarrhoea because they no longer produce lactase. This can affect 5-10% of people in Northern European countries and more in Africa and Asia where drinking milk is less common. The solution? Don’t drink cow’s milk. Not even adult cows drink it.

One of the most common messages we see about the supposed importance of drinking cow’s milk is that it contains the calcium that we need for bone health. I debunked this myth in last week’s blog so I will just summarise the facts again here. Cow’s milk does contain calcium but only about 33% of it is available to us. This is the bioavailability score and is lower than for the calcium that can be found in plant foods such as almonds or kale.

Other than dairy products, the most common animal food eaten by vegetarians but not vegans is eggs. From a health perspective, the evidence for and against eating eggs is mixed. Some studies have pointed to the fact that the high levels of cholesterol in eggs can lead to elevated blood cholesterol whereas others claim that the body produces less of its own cholesterol in the liver if it is taken in through food.

The environmental impact of dairy farming versus alternatives

My main focus is on eating for health, but I also care about the environmental impact of food production and it is becoming more widely understood and dairy farming has a high environmental cost.

One of the easiest swaps that someone can do to make sure that their food intake has the lowest possible environmental impact is to ditch dairy milk and choose a plant-based milk instead. The options are growing all of the time. I prefer oat milk for the taste, but you can now also choose milks made from soy, almond, rice, pea, potato, coconut, hemp, or cashew.

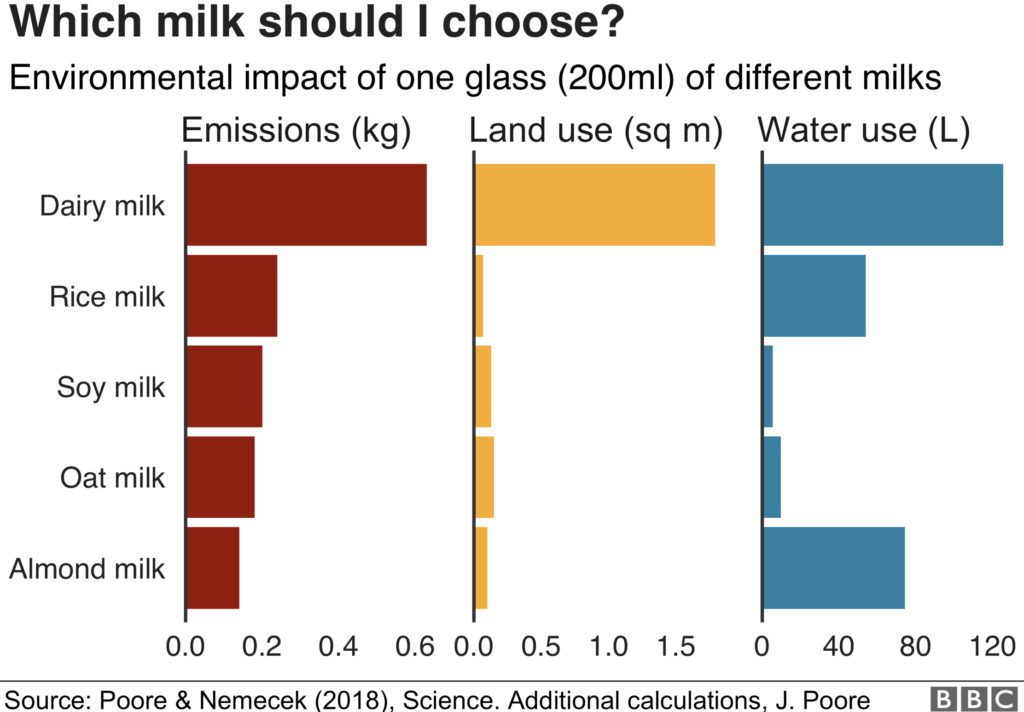

There are 3 primary areas of environmental impact to take into account when choosing between dairy or its plant-based alternatives:

- The carbon cost of production

- The area of land used in production

- How much water is used to produce the milk

In a 2019 article (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-46654042), the BBC compared the environmental impact of different milks, drawing on the work of Poore and Nemechek (2018) at Oxford University. The chart below clearly sums up the much improved environmental sustainability of plant milks when compared to dairy.

All of the plant milks perform better than dairy, with some being more environmentally sound than others. The main headline though, according to food sustainability expert Isaac Emery, discussing the Oxford study in the Guardian, is that all plant milks are better than dairy, “Drink what you want. If you’re going with plant milk instead of cow milk, you’ve already addressed most of the environmental problems that your cow milk habit was causing.”

Ethical concerns with dairy and egg production

I have to admit to putting the ethical concerns around the dairy industry to the back of my mind in the past. Either I believed the dairy industry propaganda or I was in denial. Maybe a bit of both. I believe that if we were all better informed about the ethical problems with dairy farming then most of us wouldn’t choose to consume its products. Here are some of the facts that we are not informed of:

Cows have a life expectancy of up to 20 years, but dairy cows are usually exhausted by repeated cycles of forced pregnancy by the time that they are 4 to 6 years old, at which point they are slaughtered.

Calves are forcibly separated from their mothers at birth and are fed a cheap powdered milk so that their mother’s milk can be sold to humans. Male calves are no use to the dairy industry and are raised as veal calves, being slaughtered at around 1 year of age for their meat.

If you are interested in the full facts please read this article from Compassion in World Farming: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/5235185/the-life-of-dairy-cows.pdf

One final ethical issue with vegetarian, not vegan diets, that I only became aware of a couple of years ago is the destruction of male chicks by the egg industry. Each year around 7 billion (yes, billion) male chicks are slaughtered after birth because they are not commercially useful for egg or meat production. These chciks are shredded in huge versions of the paper shredder that you might have in your home. Knowing this, I couldn’t eat eggs again, but it’s not common knowledge. Some European countries have promised to ban male chick mass slaughter but progress is slow.

To sum up, I hope that this brief explanation of some of the key differences between vegetarian and vegan diets has been enlightening even if it has been surprising, shocking or worrying. For me, one of the main problems that we face in making good food choices is a lack of honest and detailed information available to us through mainstream media channels. Hopefully, this article has helped to address this problem and given some people the confidence and drive to switch to a solely plant-based diet.